Attempting to Command the Winds

Sir Thomas More declared if his head would win Henry VIII a castle in France, it would not fail to go off. No Château; head gone. Welcome to the salon…

One evening during the sixteenth century, two men were strolling through the grounds that now encompass Roper’s Garden, a lovely little park off Cheyne Walk in London. One of them was the medieval humanist Sir Thomas More, who owned the land. The other, whose arrival had come as a surprise, was his boss. Imagine: Just yards away from where I was sitting, Henry VIII had walked along with his arm around More’s neck! As soon as the king left, More’s son-in-law asked if he was happy given he had been treated with a level of warmth the king had never shown to anyone except Cardinal Wolsey. More answered, “I find his grace my very good lord indeed; however, son Roper, I have no cause to be proud thereof, for if my head would win him a castle in France, it should not fail to go off.” (1) The last sentence reverberated as I watched the flag atop Chelsea Old Church billow below drifts of wispy clouds. The building is significant because it contains a chapel More commissioned in 1528 to serve as his private place of worship.

It was one of the buildings on his property, which extended from the edge of the River Thames toward what is now King’s Road and from Milman’s Street to Old Church Street. The acreage also held meadows, orchards, and a variety of gardens; and there was a wharf jutting into the river where he kept his barge at the ready to take him to Westminster or Hampton Court when the whims of the king demanded it. (2) More’s residence was demolished when Sir Hans Sloane purchased it in 1737 so all that remains of it are fragmentary walls shoring up the cellars of a row of homes on Beaufort Street. (3) The garden surrounding me was named during a dedication in 1964 to commemorate the fact that More had given the parcel of land to his daughter Margaret as a wedding gift when she married William Roper in 1521—the son-in-law he addressed above. The area was bombed during the Blitz of World War II and the church sustained so much damage, it had to be rebuilt. The structure and More’s chapel tucked inside it were restored as closely as possible to the originals under the guidance of the topographical historian and architect Walter Godfrey. (4)

More and his family worshipped there regularly and he sometimes assisted at the celebration of mass. (5) Illustrating what a complex legacy he left, he has been lauded as devout and his friends considered him kind and just, while biographer Jasper Ridley described him as a “nasty sadomasochistic pervert who enjoyed being flogged by his favorite daughter as much as he relished flogging heretics, beggars and lunatics in his garden.” (6) The latter is not far-fetched, as More left proof of his hatred of heretics in a declaration he wrote that is carved into a black marble tablet on the south wall of the chancel inside the church. Parish records show that More erected the shrine in 1532, just three years before his death, and that it was at some point during the restoration that the word “heretics” was replaced with a blank space. (7) This seems odd to me given how the term would have been stripped of its power by the time the church was rebuilt in 1958.

Wondering which view of him was closer to the truth, I walked to a statue memorializing the venerated man near the church. His hunched presence was so palpable, it felt as if he might unclasp his hands and step down from the frozen stance at any moment. A surprising choice of color for his skin, the sheen of his gold face did little to uplift his weary expression. The only other visual I’d seen of him is the portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger hanging in the Living Hall at The Frick Collection in New York City. The painting makes it clear the Lord High Chancellor of England was a man upon whom great honor had been bestowed. The portrait of More’s arch nemesis Sir Thomas Cromwell, also by Holbein, hangs on the opposite side of the fireplace, the depiction of the man who would help bring about More’s undoing just as filled with symbology.

It’s a brilliant installation because the enemies are sentenced to looking at each other day-in and day-out, and the distance created by the monumental fireplace surround seems a necessary separation still. When I first saw them in the room, I wondered if Holbein had consciously painted them so that they would face-off when hung on the same wall as they were: He would have known their rivalry was contemptuous, after all. More’s last days spent within his stately home near where I stood would have been unsettling because he was forced into a sudden retirement much poorer than he had been when he entered Henry VIII’s service—his income of £100 a year a paltry amount compared to his former wealth. He declined a stipend of £5,000 that the clergy offered him because he said he’d rather see all of it cast into the Thames. (8)

He explained his statement by saying he wanted rest and peace instead of riches and honors, which is understandable given he had been attempting to serve an uncontrollable king for several decades by then. He seemed quite aware of the danger he was in given the statement he made to his son-in-law and this caveat in his book Utopia, which hinted that he was grappling with a powerful force in Henry VIII: “You must not abandon the commonwealth for the same reasons you should not forsake the ship in a storm because you cannot command the winds.” (9) Moving around to the back of the statue, I noticed how the thin typeface proclaiming More a saint seemed so slight measured against the density of the figure in its heavy black cloak looming above it. I’ve never understood how a man who claimed to be so pious could feel no qualms about setting people ablaze; then again, I’ve never been involved in a religious war. With a deep heaviness permeating the mood, I had one more stop to make before letting go of the eerie echoes of Tudor history.

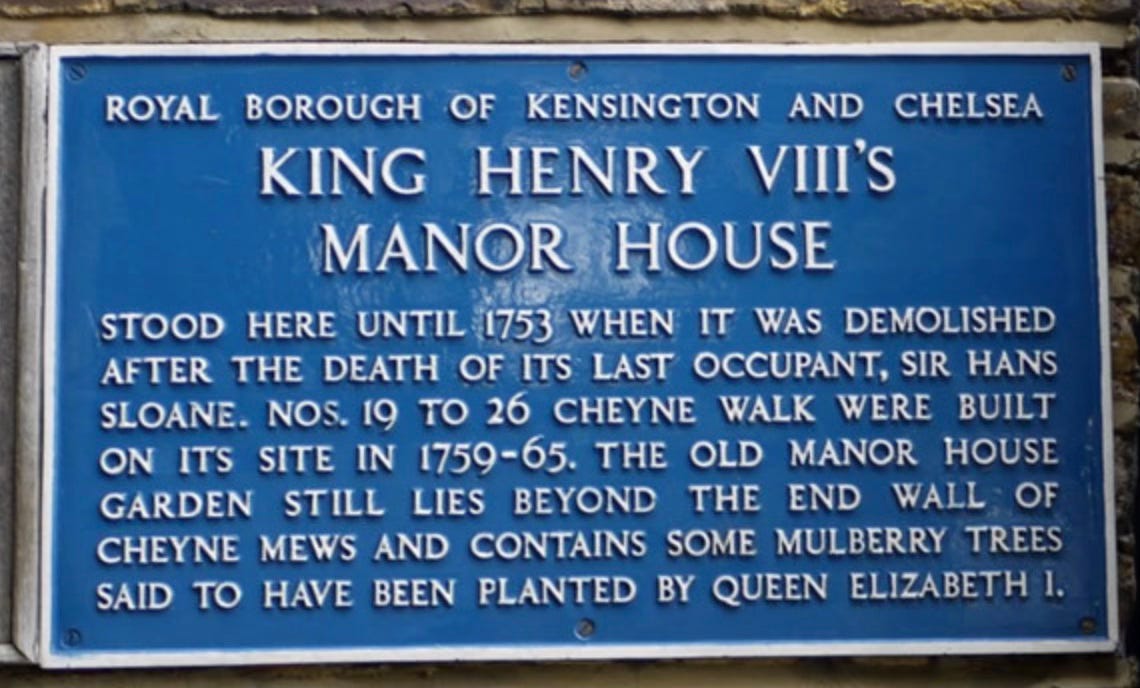

I walked five blocks east of the church to stand in front of an address where Old Chelsea Manor House once existed. All that’s left of the home owned by Henry VIII is a plaque mounted on a wall along Cheyne Walk that proclaims it was there. In 1557, Anne of Cleves, Henry’s fourth wife, died there; and his sixth and last wife Katharine Parr occupied the same dwelling when she was charged with the care of Elizabeth, Henry’s daughter with Anne Boleyn. More had never supported the king’s quest to marry Anne. As Henry pushed forward with his plans to wed her, historians deem More’s relationship with the couple “an uneasy truce,” which dissipated when the chancellor refused to attend Anne’s coronation and wouldn’t accept Henry’s claim that his first marriage to Katherine of Aragon was illicit. After he was arrested, More languished in the Tower of London for over a year before he was charged with treason. His conviction was hardly in doubt given the indictment claimed one of his crimes was depriving a king of his royal dignity. (10) In A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation, which More penned in his cell, he proved how the struggle he faced was deeply personal when he asked, “Is it not then more than shame that Christ shall see his Catholics forsake his faith?” (11)

Once he was officially charged and put on trial, the jury deliberated for only fifteen minutes before finding him guilty. Though it is rumored his daughter Margaret brought his body to Chelsea Old Church to be buried in the tomb he designed for his remains there, most reports place his body in the Church of St. Peter ad Vincula within the Tower of London. This means he will essentially spend eternity imprisoned in that notorious building, a fact that makes it fitting the statue near Chelsea Old Church presents the face of a doomed man. But I have to wonder whether it was his true countenance in the end or whether it was the artist’s interpretation of his mood given the events that led to More’s beheading were so well known by the time the work of art was created in 1969. This notoriety wasn’t immediately achieved, as the king and his counsellors tried to prevent anything from being known about the man by immediately banning publications about More’s life and the trial. They initially succeeded but once the restrictions were relaxed, More’s complex story fascinated people. (12) He was certainly wise to the king’s true nature, and, though his head did not win Henry a castle in France, it did not fail to come off just as he predicted it could.

The salon question for today: What do you think made the men who served Henry VIII continue to put themselves at risk when they knew how dangerous he could be?

A version of this piece was published in my bookThe Modern Salonnière. You’ll find it, my latest book Lives Illuminated, and all my books on my Amazon author page. Print versions from Bookshop.org are linked here. You’ll also find a number of them on Kindle. To see the sources for the footnotes, click through to my footnotes page.

Do you think these men had a choice? Was it even possible to “retire” from the king’s service and slip away to a peaceful life in the country?

Fascinating read! Power is seductive and, as JoAnn says, maybe each one thought they would be the exception to the rule and could cross the King with impunity - wrong!