Under the Storied Window

One of history’s lauded poets suffered from rejection in his own country during his lifetime. How did Percy Bysshe Shelley cope? Welcome to the salon…

A note to thank everyone who is reading and a bit of a shift—I’m going to be posting every other week for the foreseeable future to make way for a few new work projects. Also, though I’m continuing to share all of my posts for free, I have enacted an option for paid subscriptions in case there are those of you who would be willing to subscribe. If you’d prefer not to commit to a monthly or annual subscription, I’ve enacted a donate button (midway down) that allows for one-time or intermittent infusions of financial support.

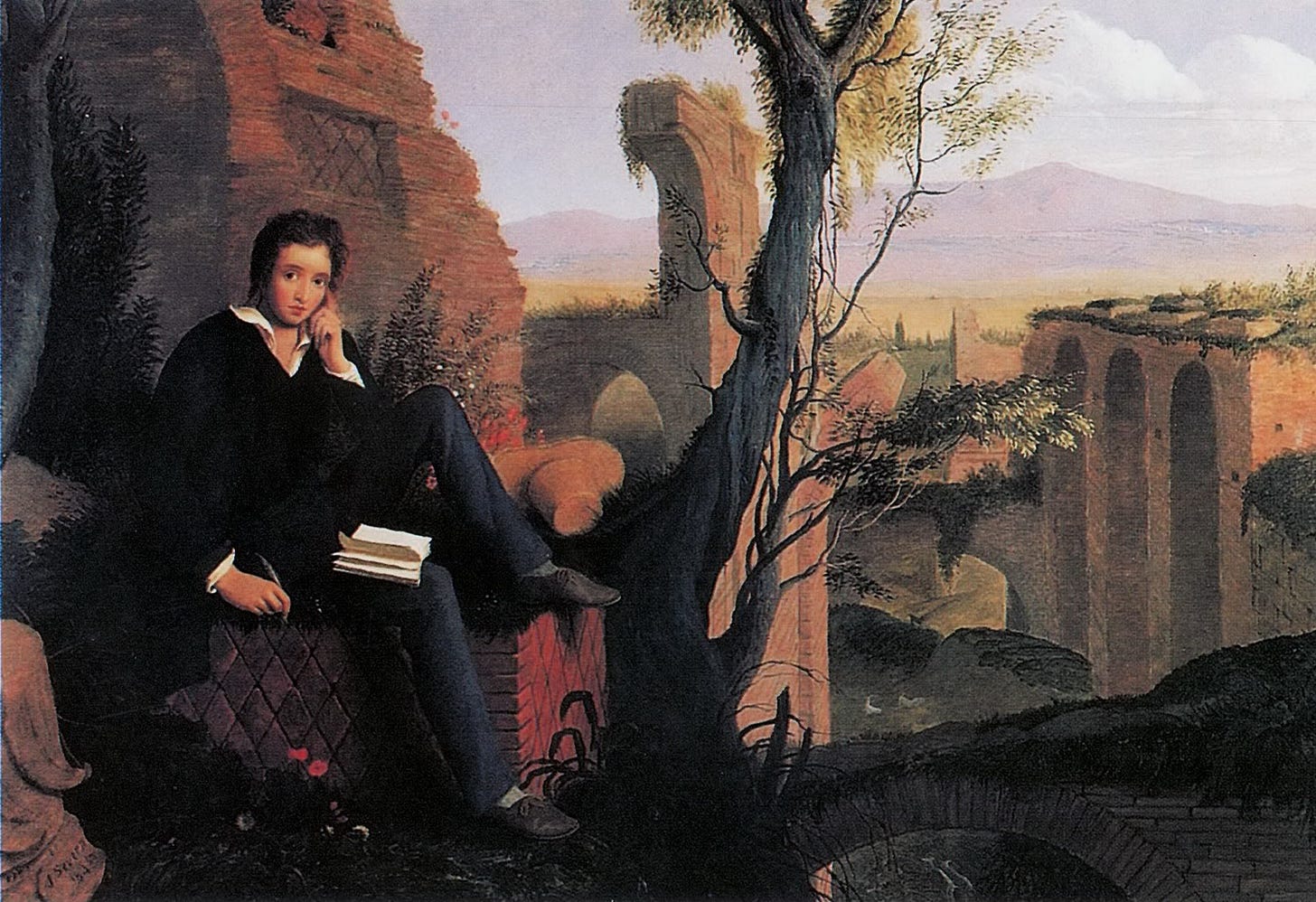

One of the things that has always fascinated me about Percy Bysshe Shelley is how he was dogged by a lack of confidence because his writing was received so poorly by the critics and the reading public in his own country during his lifetime. Looking at his oeuvre now and knowing the influence he has had on the development of literary history given he died so young makes it astounding that he was made to feel inept—a consequence that stemmed from the era in which he tried to find his footing. His letters are filled with angst about his work not being published, particularly while he, his wife Mary, and her stepsister Claire Clairmont were making their way around Italy between March of 1818 and July of 1822. The dispatches to his friends that describe his reactions to the country are a pleasure to read because he is seeing everything around him filtered through his poetic sensibilities. One of the cities they visited was Milan, and a letter he wrote to Thomas Love Peacock on April 20, 1818, describes his experience in the Duomo di Milano there.

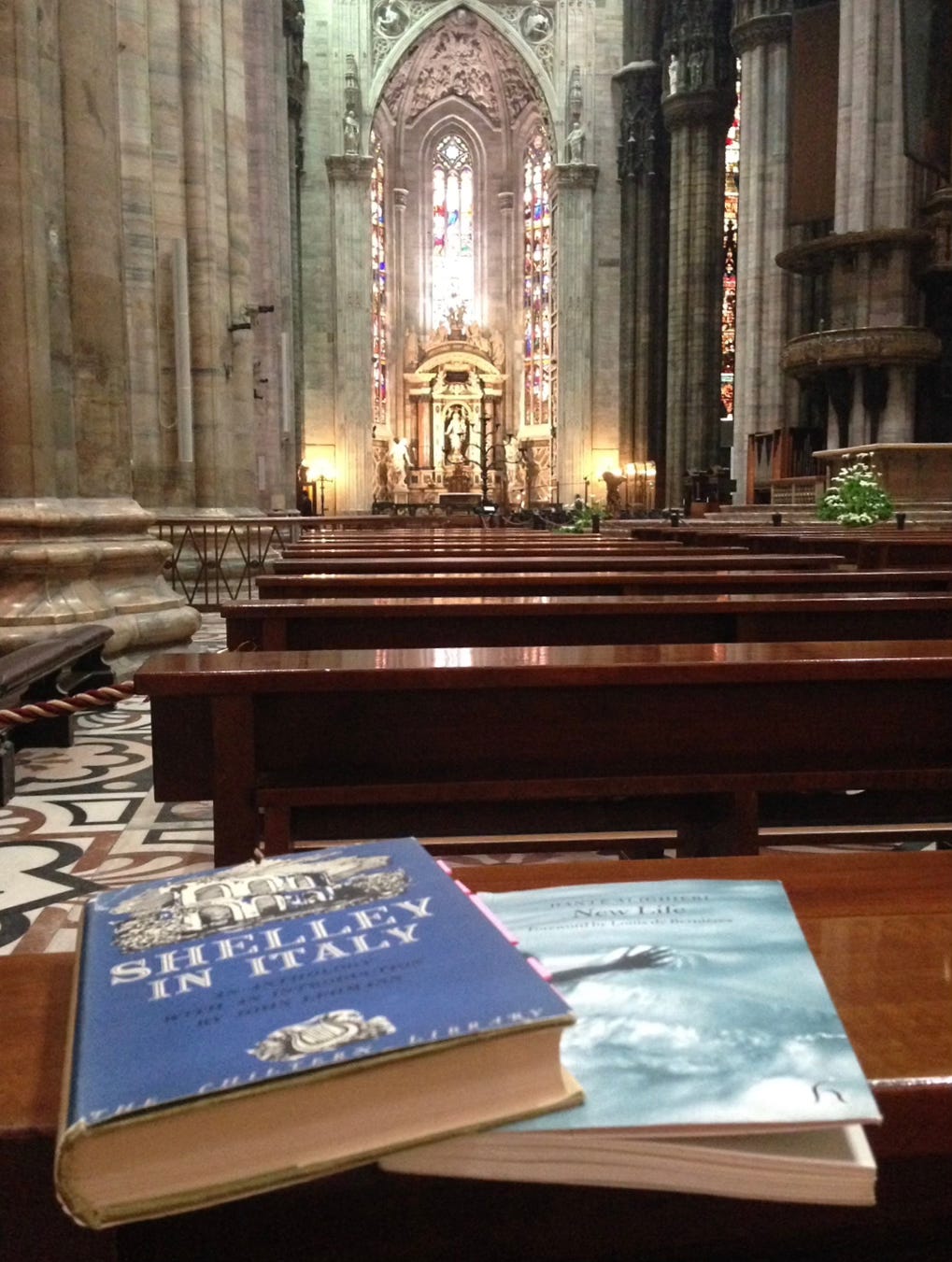

“This cathedral is a most astonishing work of art,” he told his friend. “It is built of white marble, and cut into pinnacles of immense height, and the utmost delicacy of workmanship, and loaded with sculpture. The effect of it, piercing the solid blue sky with those groups of dazzling spires, relieved by the serene depth of this Italian heaven, or by moonlight when the stars seem gathered among those clustered shapes, is beyond anything I had imagined architecture capable of producing.” (1) During one of my trips to Milan, I took a pilgrimage to the Duomo with two books in hand—Shelley in Italy and Dante Alighieri’s The New Life, choosing the latter because Shelley told Peacock he passed several afternoons in the church reading Dante’s works. The closer I drew to the exterior of the building, the more impressed I was that anyone had ever had the courage to create such an intricate façade! The stories that spring to life in the sculptures are told by downcast figures sentenced to supporting great columns on their backs for as long as the building stands. They are surrounded by bas reliefs depicting humanity struggling just as valiantly within their own allegorical universes. The transition from these mythic masterpieces that gleamed in the strong sunlight made it necessary to pause after the gigantic door closed behind me so my eyes could adjust to the muted light inside. I hoped to find a pew as close to the section of the cathedral Shelley described but I had to choose a seat fairly far away so as not to disburb churchgoers worshiping near the pew he had occupied.

“There is one solitary spot among those aisles, behind the altar, where the light of day is dim and yellow under the storied window, which I have chosen to visit, and read Dante there,” he wrote 197 years before I entered the cavernous space, almost to the day. I pulled Dante’s treatise on courtly love and the book of Shelly’s Italian works from my bag and placed them on a shelf formed by the top of the pew in front of me. Looking around I saw Shelley’s lyrical descriptions manifest before my eyes. “The interior, though very sublime, is of a more earthly character, and with its stained glass and massy granite columns overloaded with antique figures, and the silver lamps, that burn forever under the canopy of black cloth beside the brazen altar and the marble fretwork of the dome, give it the aspect of some gorgeous sepulcher,” he wrote before turning to more distressing matters that exposed his doubt about his abilities. “I have devoted this summer, and indeed the next year, to the composition of a tragedy on the subject of Tasso’s madness, which I find upon inspection is, if properly treated, admirably dramatic and poetical. But, you will say, I have no dramatic talent; very true, in a certain sense; but I have taken the resolution to see what kind of a tragedy a person without dramatic talent could write.” (2)

As we now know, his literary gifts were not to blame for his lack of acceptance in England; the issues that made him unpopular were his liberal opinions about free love and open marriage, and his radical political views for his time. “I am regarded by all who know or hear of me, except, I think, on the whole, five individuals, as a rare prodigy of crime and pollution, whose look even might infect,” he said in a letter to Peacock from Rome. “I write nothing and probably shall write no more. It offends me to see my name classed among those who have no name. If I cannot be something better, I had rather be nothing…” (3) He wrote to Leigh Hunt from Pisa to tell the publisher he had not bothered to inquire as to how his writings were being received because he didn’t want to be upset by the news. “My faculties are shaken to atoms and torpid,” he added; “if Adonais had no success and excited no interest, what incentive can I have to write?” (4) His suffering is all the more poignant because Shelley’s output during his four-year wanderjahr was significant and not only in quantity but in quality. John Lehmann, who selected the works that are included in Shelley in Italy, says the amount of exemplary writing he produced “would have done credit to the most fluent of poets, especially when we remember the troubles he was laboring under so much of the time.” (5)

Among these challenges were financial woes and the fact he measured his stature and poetry against the growing popularity of Lord George Gordon Byron. “When he joined Byron in Ravenna, the contrast of his neglect with Byron’s success deepened his depression, though there is not the slightest trace of envy in his high estimate of Byron’s place in the literature of his time,” Lehmann wrote. As Shelley’s self-doubt grew, he admitted to Edward Trelawney, “If you ask me why I publish what few or none will care to read, it is that the spirits I have raised haunt me until they are sent to the devil of a printer.” (6) He told Peacock, “I am devising literary plans of some magnitude. But nothing is more difficult and unwelcome than to write without a confidence of finding readers; of ever producing anything that shall merit them.” (7) Near the end of his short life, he posted a letter to John Gisborne from Lerici that said, “I stand, as it were, upon a precipice which I have ascended with great, and cannot descend without greater peril, and I am content if the heaven above me is calm for the passing moment.” (8) This statement is ironic given any peace would be fleeting, as he died on a stormy sea less than a month later at the age of twenty-nine.

As Shelley’s life was ending, Dante’s was taking a heart-rending turn in his book, which opens with the description of his overwhelming feelings for Beatrice Portinari when he first met her—they were both nine years old. “Woe is me!” he declared, “for I shall be disturbed from this time forth!” (9) He was right to lament given he would suffer from unrequited love for the rest of his life. Being immersed in the melancholy moods of these two creative geniuses had infused the afternoon with a mellow sadness that was shattered when resplendent chords from the organ exploded, obliterating a silence that had been interrupted only by occasional and distant murmurs before. The exuberance of the music, which signaled the end of a service for a small group of parishioners who had gathered for mass far across the nave, ended all possibility for quiet reflection so I made my way down one of the dark aisles toward the narthex, pausing just long enough to take one last look around to savor that I had spent time in a building in which Shelley had sat reading. Once I heaved open the door, the shock of drenching sunlight was extreme. Squinting into the brightness, I made my way to a small café tucked beneath a colonnade hemming the piazza.

I chose a seat with a splendid view of the building that Shelley so rightly called “a most astonishing work of art” and ordered a glass of wine feeling a sense of gratitude toward the friends to whom Shelley had written because they saved his letters. They are so valuable in my eyes because they bear witness to the fact that a lauded writer who felt so ignored could continue to create in spite of this. I wanted to share this aspect of Shelley’s story with other writers who may not have known how he struggled so he can serve as a beacon. He certainly has been one for me given he kept writing even when he was beaten down by hopelessness. This gives me the courage to continue my creative work in spite of the fact that this facet of my writing life has never financially supported me. This doesn’t mean I could stop writing—it is the blessing and the curse for anyone with a passion for putting words on the page, which I suspect Shelley knew all too well.

The salon question for today is: Do you think historical figures who have struggled in the past can serve as examples for those of us feeling uncertain today?

A version of this piece was published in my bookThe Modern Salonnière. You’ll find it, my latest book Lives Illuminated, and all my books on my Amazon author page. Print versions from Bookshop.org are linked here. You’ll also find a number of them on Kindle. To see the sources for the footnotes, click through to my footnotes page.