The Fragile Nature of Testimony

Colette claims her writing career would not have come to pass were it not for her first husband. Her third husband explains why. Welcome to the salon…

This is one of three salon explorations featuring Colette. To enjoy the full series, click through to the first one and then after reading this, the second one, click through to the third.

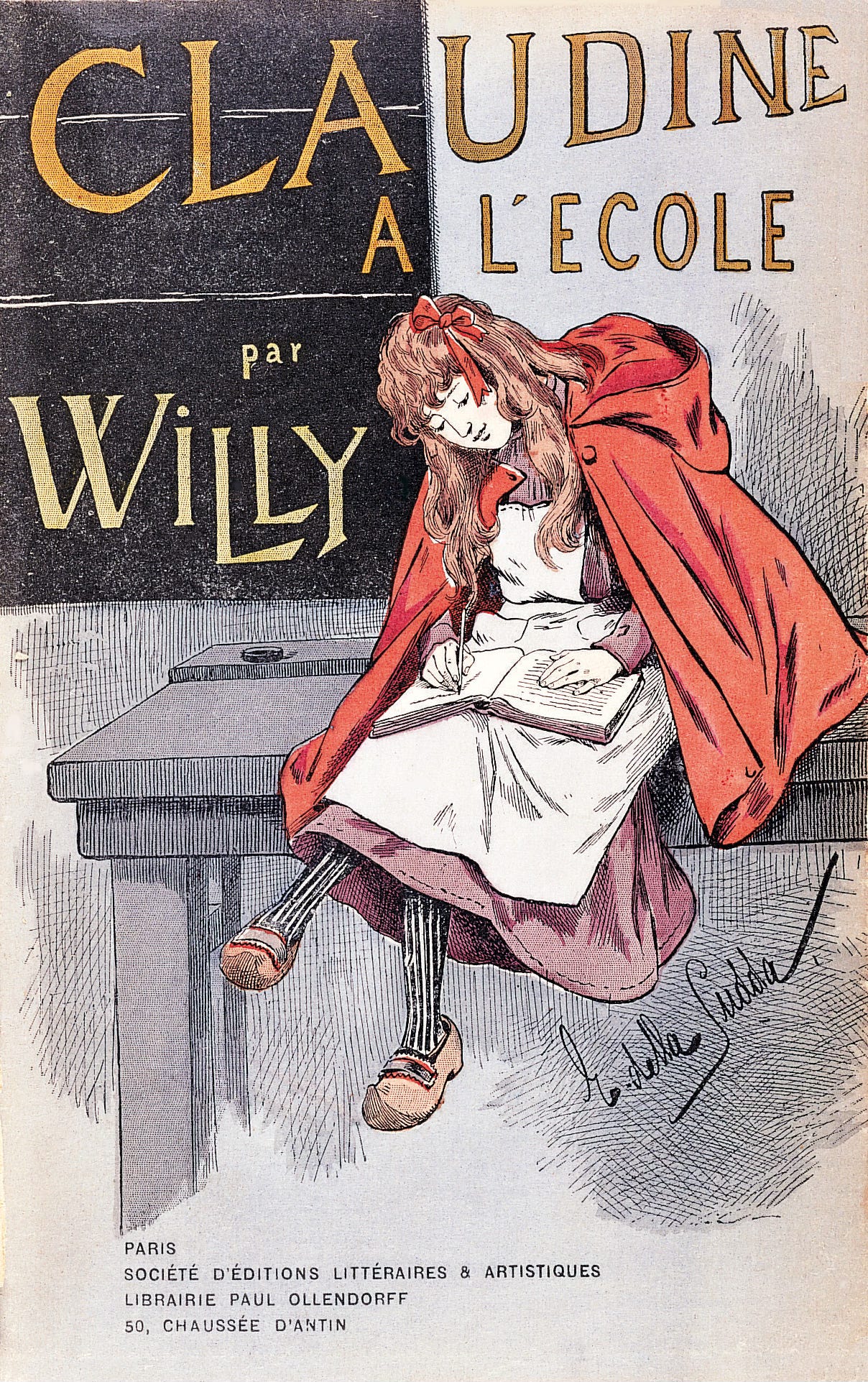

Maurice Goudeket, Colette’s third and final husband whom I introduced in the last salon exploration confirmed my suspicion that had her first husband Willy not locked her into a room until she produced a certain number of pages each day, she wouldn’t likely have become a professional writer. He wrote in his book Close to Colette, “She was sincere when she used to declare that if circumstances had not led her to write, she would never have done so all her life long. There may well never have been a person with less of a vocation to write, and as soon as one knew her well one ceased to be astonished at this.” (1) Colette’s drive to put words on a page wasn’t about being successful at writing; she simply strove to accomplish every task with as much acumen as possible. Maurice said this was the case because she lived so intensely that to be alive was her occupation.

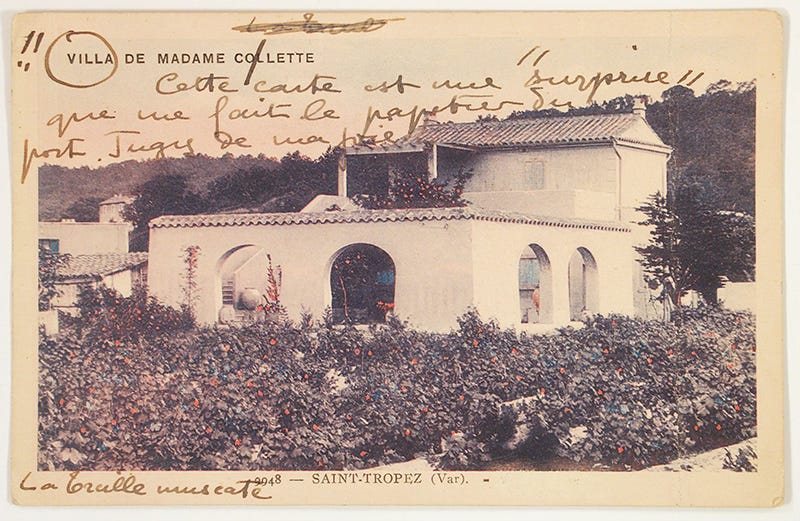

“It was not a more novel activity to write than, for example, to make a pair of sabots,” he explained. “Each needed to be performed as well as possible, with care and attention to detail.” (2) Given this applied most particularly to her written pieces, it’s no surprise she made her mark in almost every literary genre known to man (and woman). She wrote novels and short stories, of course; but she also penned plays, screenplays, and journalism—the latter including stints as a literary critic, a crime reporter, a social columnist, a war correspondent, and just about every subcategory in between. Maurice respected her fiction the most, citing her novel La Naissance du Jour [Break of Day] as particularly powerful. Set in a small cottage they owned in Saint-Tropez, he said it was his favorite of all of her books because it was autobiographical.

“Everything is in it: ‘La Treille Muscate’ [their home], the garden, the vineyard, the terrace, the sea, the animals,” Maurice explained. “Our friends are called by their real names. Colette puts herself into it, describing herself in minute detail. Never has she pushed self-analysis so far.” He added that all of the allusions to her past in the book were authentic, including the letters her mother wrote to her, which Colette quoted verbatim. About her ability to capture the essence of their time in the South of France, he wrote, “The odors are those which still delight my nostrils. I have known those blue nights, I hear the wheezing of the cicadas, I feel the buffeting of the wind, my hand lingers on the warm wall. Everything is there, except that La Naissance du Jour evokes the peace of the senses and a renunciation of love at the moment when Colette and I were living passionate hours together, elated by the heat, the light, and the perfume of Provençal summers.” He said the novel was “bathed in poetry and of unequalled destiny, richness, and eloquence.” (3)

Though Maurice could be effusive about her and her writerly abilities in his book because she was gone by the time he wrote it, he said he never praised her in person while she was alive without seriously considering what he would say and how he would say it because any flattery, even if it was true, made her uncomfortable. Though Colette wrote about her husband most profusely in her letters, she did not mention him in La Naissance du Jour, which he claimed did not surprise him because she was prone to austerity. Her reticence toward him also shows up in her memoirs when she described him in rather platonic terms, as she did here in L’Étoile Vesper, The Evening Star, which she began writing in 1943 when she was seventy: “Night, O night, sighs the Arab chant, O thou Night once more. When I embark on night in the name of rest and, if possible, sleep, she is already half-engaged in her course towards the limpidity of morning. We go to bed very late, my companion and I.” After promising she would call if she needed anything because they no longer shared a bedroom, she said, “The door closed between us, I am free not to sleep, to wander around a little, to limp unconcealed, to go and eat what’s left of the marmalade.” (4)

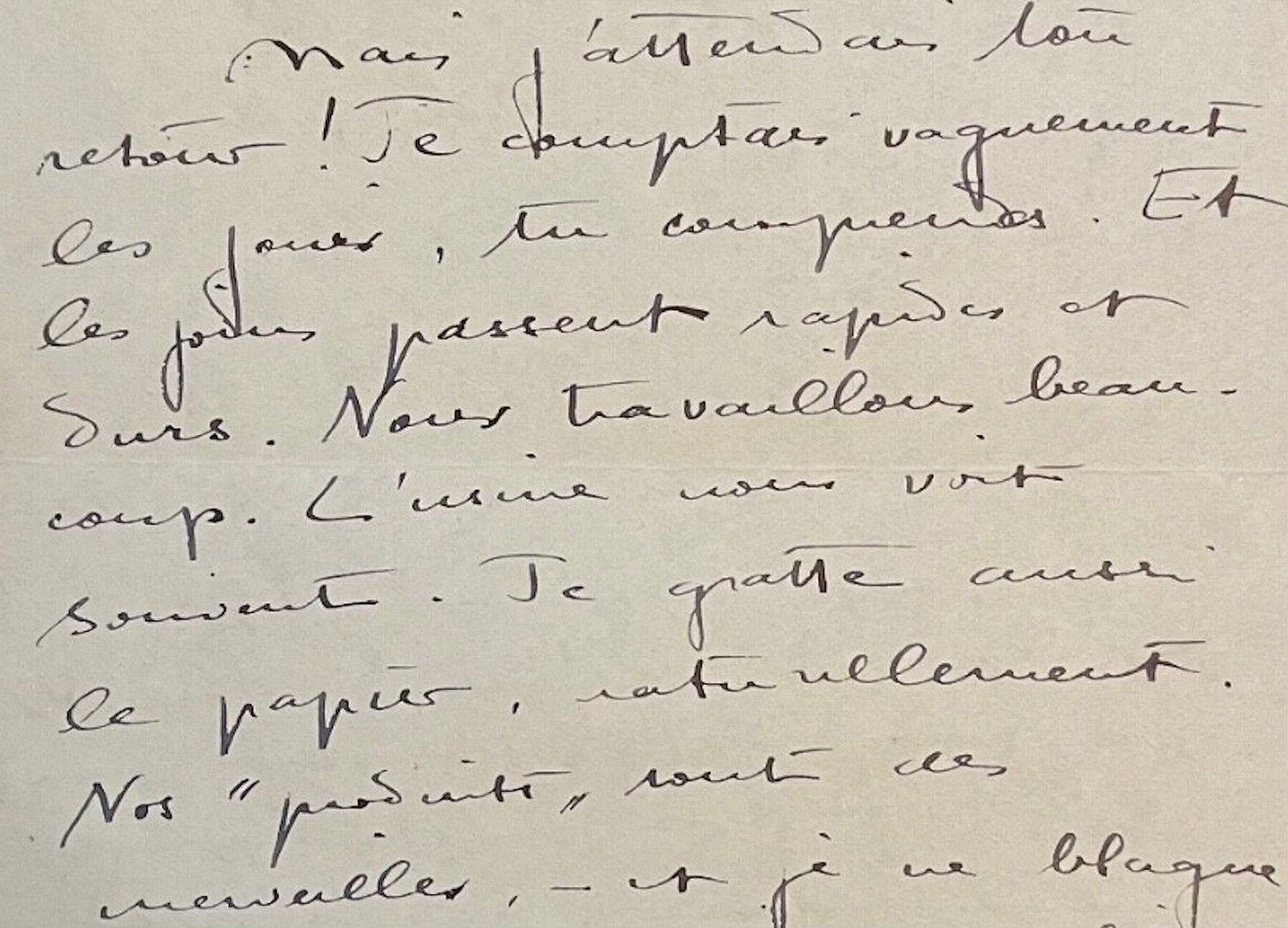

The truth of how close they were was reserved for her inner circle, as this letter to her friend Marguerite Moreno proves. “Last night Maurice and I had one of those talks that began at ten minutes to midnight and went on until four twenty-five in the morning,” she wrote. “Would you believe it? How it satisfies me to fight with a certain finesse, and to find that my partner is on the right wavelength.” (5) Literary history owes a great debt to this man who made it his mission to enlighten the world about his wife and her qualities. “I was not master of Colette’s hours of meditation as she sat at her tapestry and we respected long and trustful silences between ourselves,” he explained. “The fact remains that I owe the public, in such measure as I am responsible to it, and in spite of the fragile nature of it, my testimony as to what lay at the root of Colette’s behavior and was therefore the foundation of her work.” (6) It is evident in The Evening Star, which was published in 1946, that Colette had a love-hate relationship with this work.

“To unlearn how to write, that shouldn’t take much time,” she declared. “I can always try. I shall be able to say: ‘I’m not concerned with anything here, except this rectangular forget-me-not, this rose shaped like a jam-puff, this silence when the sound of excavation produced by the search for a word has been suppressed.’” Without a beat, she busted herself by revealing it was not quite that simple. “Before reaching my goal, I continue to work,” she explained. “I don’t know when I shall succeed in not writing; the obsession, the compulsion date back half a century. The little finger of my right hand is somewhat bent because, when writing, the right hand supports itself on it like the kangaroo on its tail. Within me a tired mind continues with its gourmet’s search, looks for a better word, and better than better.” (7) She ended the book with this insightful analogy: “On a resonant road the trotting of two horses harnessed as a pair harmonizes, then falls out of rhythm to harmonize anew. [Likewise,] the habit of work and the commonsense desire to bring it to an end become friends, separate, come together again. Try to travel as a team, slow chargers of mind: from here I can see the end of the road.” (8)

She declared she had wanted her final two books to be journals but she hadn’t conquered the knack of writing daily dispatches, which she described as “stringing together, bead by bead, day after day, a rosary whose value and intrinsic luster are relative to the writer’s power of exact observation, of assessing his own importance and that of his time.” Explaining why it was impossible for her to do so, she wrote, “The art of selection, of noting things of mark, retaining the unusual while discarding the commonplace, has never been mine, since most of the time I am stimulated and quickened by the ordinary.” Her ambiguity toward putting words on a page was never far from her mind. “There I was, vowing never to write anything again after L’Étoile Vesper, and now I have covered two hundred pages which are neither memoirs nor journal,” she explained. “Let my reader resign himself to it: this lantern of mine, burning blue day and night between the pair of red curtains, pressed close to the window like one of the butterflies that fall asleep there on a summer morning, throws no light on events significant enough to astonish him.” (9)

Near the end of her last memoir La Lanterne Bleue, The Blue Lantern, Colette had her final say about the discipline that had enthralled, annoyed, and exhausted her for so much of her adult life when she explained she felt “an insurrection of the spirit,” which “in the course of my long life I have often rejected, later outwitted, only to accept it in the end, for writing leads only to writing. I am still going to write; I say this in all humility. For me there is no other destiny. But when does writing have an end? What is the warning sign? A trembling of the hand?” She brought the book to a close with this powerful analogy: “I used to think that it was the same with the completed book as with other finished ploys—you down tools and raise the joyful cry ‘Finished!’ Then you clap your hands only to find pouring from them grains of sand you believed to be precious. That is the moment when, in the figures inscribed by those grains of sand, you may read the words ‘To be continued…’” (10)

Next week, we follow Maurice through Colette’s final years. The salon question for today: Is it surprising to you that she wouldn’t have written had Willy not sequestered her in their study given how fervently she wrote the above about her process?

A version of this piece was published in my book Lives Illuminated. You’ll find it, The Modern Salonnière, and my other books on my Amazon author page. Print versions from Bookshop.org are linked here. You’ll also find a number of them on Kindle. To see the sources for the footnotes, click through to my footnotes page.