Not Without My Notice

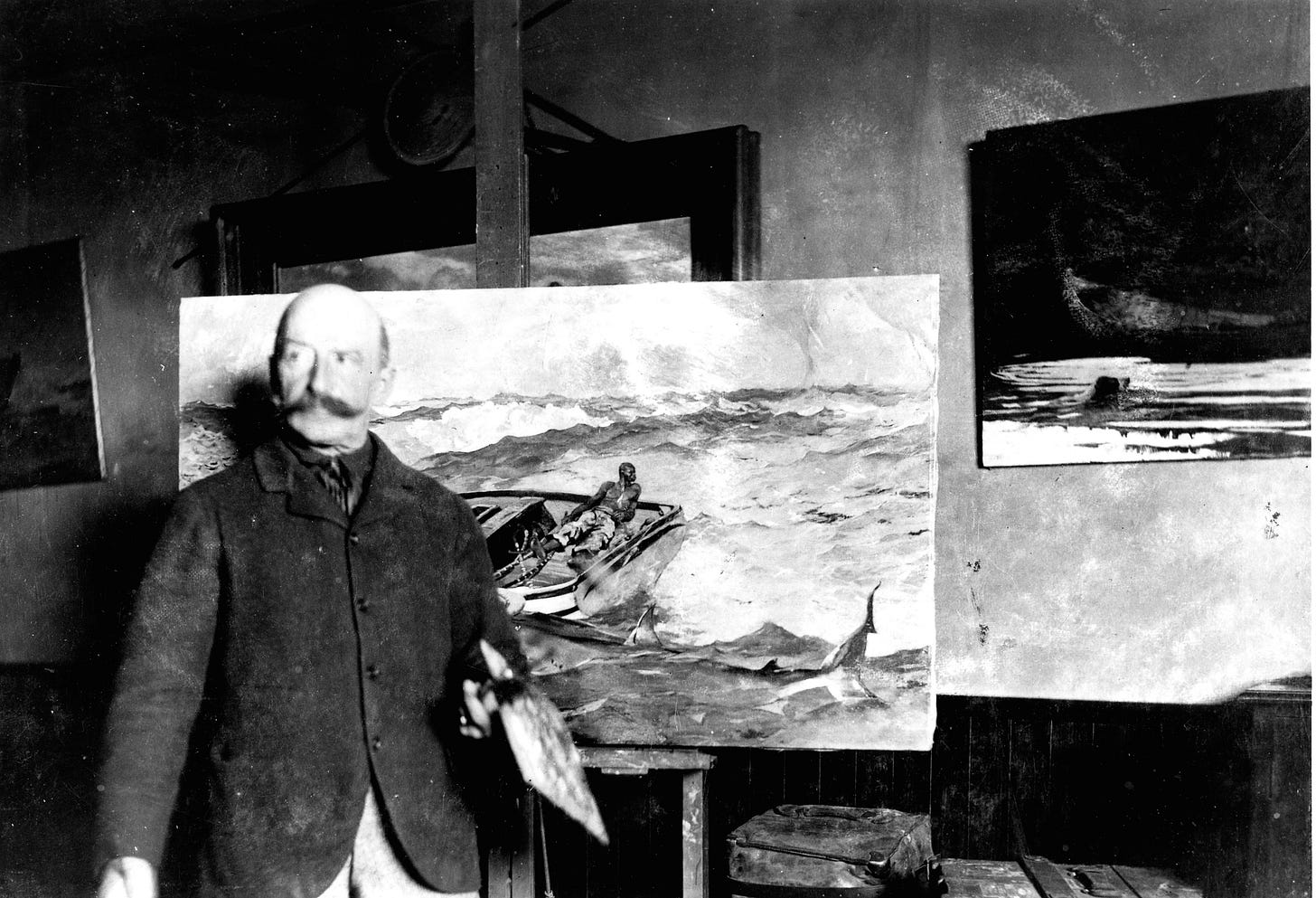

An exhibition and a restored studio bring a pragmatic Maine artist with an eye for watery drama into focus. Welcome to the salon…

“Artists should never look at pictures, but should stutter in a language of their own,” said Winslow Homer. (1) I read this statement surrounded by his salty stammering hanging in a gallery in the Portland Museum of Art in Maine. Making a slow 360-degree turn, I took in the churning effect of wind, water and waves—a panorama that captured the wrath of Neptune and brought a powerful rush. Then I came upon a thing of such quiet dignity, I couldn’t move. The luminosity of “The Fisher Girl” compelled me to stay; to study the iridescence of the frothy waves and the gleaming unfurled wings of a gull in flight, both juxtaposed against the gray gloom of wind-swept sand and tossing sea.

Grounding the scene were the girl’s earthy garments and sensible demeanor—her hair, gathered tightly into a bun; the net she carried so old-fashioned as to be ornamental as it cascaded down one side of her dress; the wind worrying the edge of her shawl as she shielded her eyes from billowing foam; the slightest hint of a petticoat peeking from beneath the hem of her dress, its ruffles pinched in gathers just above her remarkably utilitarian shoes. Leaving her behind, I was back in boats that pitched and rolled, fending off water that sprayed as it crashed ashore. I was living Homer’s point of view, which convinced me that he meant it when he said, “The sun will not rise, or set, without my notice.” (2) The morning after I saw the exhibition, I trekked along the craggy shoreline of Prouts Neck to his studio, which had just opened after being restored. As soon as the water came into view, I marveled at the chiaroscuro effect of the black rocks jutting into a glistening Saco Bay.

Though intense sunlight created the opposite effect than when the fisher girl might have walked along the lip of land drenched in fog, I could taste her reality as I picked my way along. Navigating the meandering path of dirt that had been tamped into crevices in the rocks was a challenge. I was lurching over the uneven terrain when a slender snake zigzagged across the trail near my foot and my heart skipped a beat. As I recoiled, the friend walking behind me assured me no snakes Maine are poisonous. This did little to quell the sizzle pulsing through my nervous system as we entered Homer’s domain. I laughed aloud when I spied the crude sign atop the fireplace mantle, as I knew I’d had a small taste of the life the artist had lived. “Snakes,” it declared in uneven strokes of black paint; “Snakes! Mice!”

I looked out the same window he would have peered through so many times, and felt a sense of awe at the raw beauty of the coastline. It would have been much less developed during his time so I could imagine how prevalent the reptiles and rodents would have been as he combed the shoreline for vistas to paint. Looking out from the second-story of the refuge where the panoramas he had studied splayed to the horizon line made the experience of being there so rich. I wondered if he ever looked toward where the bay seems to disappear into the sky and decided to remain settled in the chair beside the blazing fire, a few slow drags on his pipe convincing him to let the spray take the rocks without his scrutiny for a change. I doubted it given what a practical human being he was.

Even when he described the fact that he was living a life he loved, he was quite down-to-earth: “That I am in the right place at present time is no doubt, as I have found something interesting to work at, in my own field and time and place, and material with which to do it.” The novelist Henry James noted Homer’s talent by pointing out he chose the least pictorial scenery and subjects for his paintings only to make the art representing them highly pictorial. (3) By being able to visit Homer’s studio, I saw so clearly how he had lived the last years of his life steeped in brine and fog, salt-spray and glinting chop, so much so that he forcefully brought the practical aspects of man’s relationship with the ocean to life.

His premise that artists must stutter to find a language of their own is just as true for writers, and I left there determined to find the landscape that would turn my stuttering into something I hoped would be as worthy as his body of work. I had been writing for decades by then but I had yet to realize my creative life does not require a daily access to vistas. It does demand a certain stillness I had not yet achieved because I was traveling so much. By staying put, I have come to see that my fascinations transcend time and place as I take in the sweep of the centuries and bring forward those living whose stories express something that I see as worth mentioning.

The salon question for today is: Do you think it is possible for a clarity of purpose to come early in life or does it require the experience gleaned through living long enough to reach the final decades?

A version of this piece was published in my book The Modern Salonnière. You’ll find it, my latest book Lives Illuminated, and all my books on my Amazon author page. Print versions from Bookshop.org are linked here. You’ll also find a number of them on Kindle. To see the sources for the footnotes, click through to my footnotes page.

Thanks for introducing me to this artist. To answer your question, I think clarity of purpose comes early for some, but others are not so lucky.