An Unknowable Future

Remnants of a Roman bath at the Musée national du Moyen Âge in Paris have witnessed a remarkable sweep of history. Welcome to the salon…

Striding along the same route a man trod during the fourth century brings a visceral understanding of history that is impossible to glean from books or historical documents, as helpful as they may be. You can test the theory for yourself by approaching the Thermes de Cluny in Paris from the direction of the Petit Pont. Once a Roman bath at what is now the busy intersection of the Boulevards Saint-Michel and Saint-Germain, the jagged remnants look remarkably primitive attached as they are to the medieval mansion holding the Musée national du Moyen Âge. Though powerful, they only hint at what was once an imposing structure, the rest of which was destroyed by marauding tribes in ancient times. The only sections that were never ruined include a U-shaped fragment that reads like a primordial throne large enough to accommodate Zeus were he inclined to visit, a pair of L-shaped walls, and a massive vaulted chamber known as a frigidarium because it would have originally held a cold pool. The other walls would have surrounded the Tepidarium (warm pool) and Caldarium (hot pool) before they were damaged.

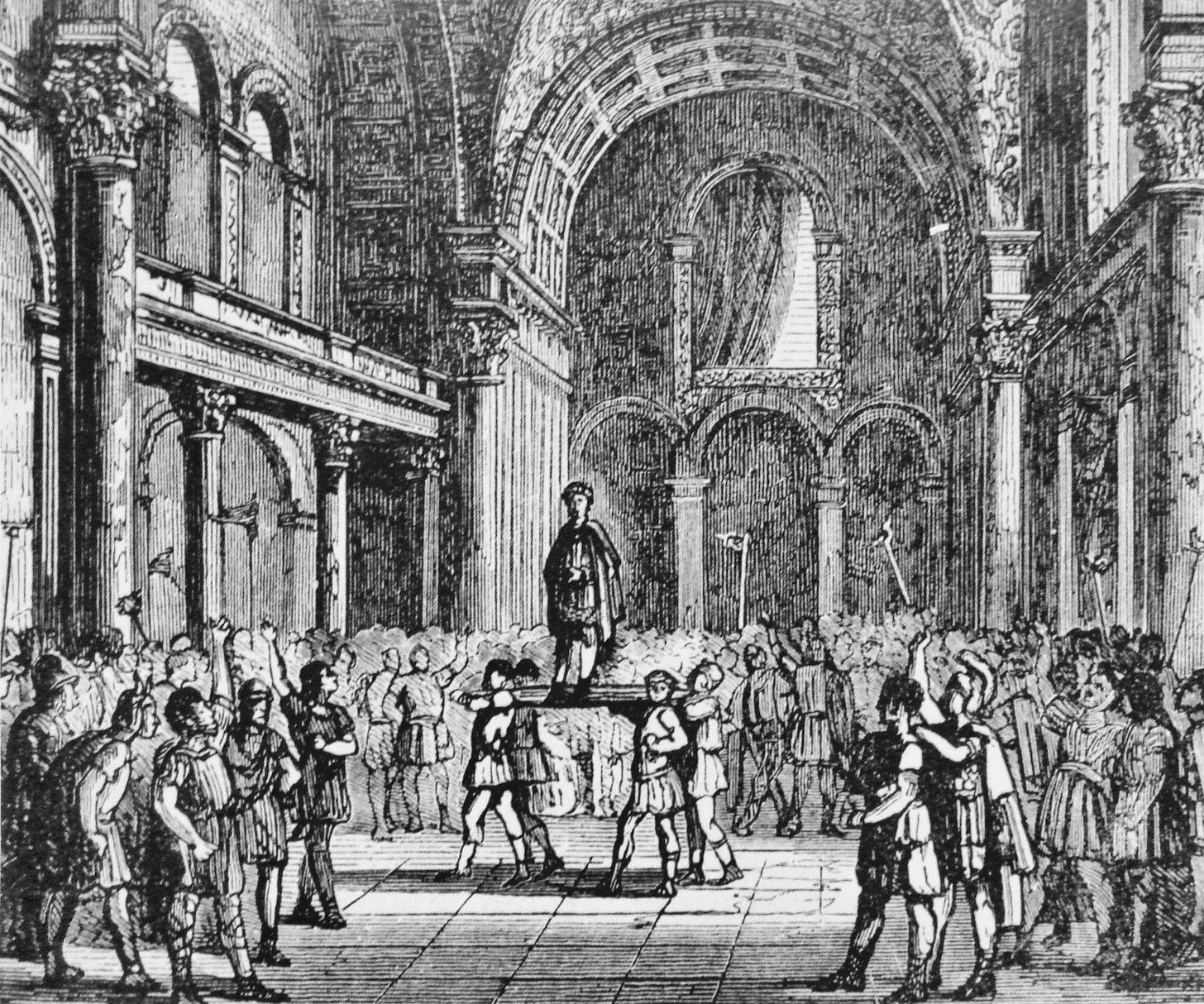

Architectural historians believe these artifacts have occupied the corner since sometime between the first and second centuries A.D. During their heyday, the residents of Paris, then known as Lutetia, enjoyed a spa-like experience within the complex that was de rigueur when the Romans dominated Europe. My interest in the baths was piqued when I found an etching of a Roman Emperor known as Julian the Apostate being carried through the tall spaces of the Thermes on a shield. His soldiers were declaring him sole Augustus in the backdrop with its massive columns topped with fanciful capitals that no longer exist. The Scottish Byzantinist Robert Browning, who wrote The Emperor Julian, noted that the sections of the baths that haven’t survived would have been destroyed during civil unrest a century before Julian arrived so the drawing is an imaginative construct. (1) Though it’s unclear whether the newly crowned emperor ever set foot in the frigidarium, he likely passed by the remnants as he crossed the river and made his way through the neighborhood from his command center, a robust fortress surrounded by ramparts on the Île-de-la-Cité.

In order to comprehend how small the footprint of the city was when Julian was in residence, I decided to make my way to the Thermes from the corner where the maps of Roman Paris situate the fortress. It predated the Palais de la Cité, Conciergerie, Palais de Justice, and Sainte-Chapelle that now rise from the plat of land. To imitate the only route he could have walked in 360 A.D. given the Petit Pont was the sole bridge between the island and what is now the Left Bank, I traversed the river across it and trekked up Rue Saint-Jacques to Boulevard Saint-Germain. As I turned the corner to approach the museum, I marveled at the scale of the ragged walls splayed beyond the medieval garden, though I’d seen the artifacts with their tattered edges several times. There was something about their roughness that made them seem brutally arrogant.

The remnants would have been demolished in 1485 by Jacques d’Amboise, the Abbot of Cluny who built the turreted mansion that now adjoins them, had he not been a fiscally responsible man. Dismantling the baths would have added an exorbitant amount to his construction costs so he used parts of the old structure to support the new one—a frugal move that bestowed a blessing on lovers of ancient architecture. When the mansion was finished in 1510, it was christened the Hôtel de Cluny because it would be the abbot’s home when he was in town and would house the monks he oversaw. (2) The Musée national du Moyen Âge took over the building in 1843 when Alexandre du Sommerard, who owned the mansion from 1833 to 1842, bequeathed it to the city to serve as a venue for the artifacts he had avidly collected. (3) Entering the museum’s courtyard is like sliding through the looking glass, the feel of otherworldliness enhanced by a dilapidated well with a half-eaten-away gargoyle gaping at its edge.

The meandering spaces on the first floor are dimly lit to protect the artifacts within them, which made it a shock to step from the close-knit warren of rooms into the immense frigidarium, the only fully-constructed space that existed in the original Gallo-Roman compound to have survived. (4) The cavernous room is chilling even without the coolness of the pool glinting in its center because it’s difficult to process that the stone and bricks composing its walls witnessed so many primitive acts as the city was conquered, rebuilt, ransacked, patched up, and plundered again. Gaul, as France was known when Julian was in town, was a treasured prize for ambitious men like him, as was the designation of emperor. He was prepared to achieve the latter by whatever means necessary, the path he chose a treasonous act of declaring himself emperor while his cousin Constantius II held the title. To cover his culpability, Julian claimed it was his soldiers who insisted he accept their nomination as a reward for his leadership on various battlefields.

Constantius had sent Julian to Gaul to get rid of him—he expected him to die in combat along the way given he was inexperienced at war. After a series of skirmishes that proved his cousin wrong, Julian spent several contented winters in Lutetia reading two books he saw as the perfect manuals to prepare him for a career as a great leader: Plutarch’s Lives and Julius Caesar’s Commentaries. (5) His desire to rule wasn’t far-fetched: He had a royal lineage, though it was the offspring of his uncle Constantine the Great who claimed the right to the throne, not his father’s. The word Apostate, which has long been attached to his name, designates his predilection for worshiping the Greek gods, which made him the last ‘pagan’ emperor. By the time he came into power, he had spent a decade concealing his loyalty to Hellenism, which he embraced when he was educated in Athens, because Christianity had become the accepted religion of the day.

His respect for the mythic panoply is evident in his letters, which are peppered with phrases like “Zeus be my witness!” and “How, in the name of Zeus, did you behave?” (6) He also proclaimed, “I feel awe of the gods. I love, I revere, I venerate them and in short have precisely the same feelings toward them as one would have towards kind masters or teachers or fathers or guardians or any beings of that sort.” (7) It’s natural that he would have been looking for father figures, as he had survived a traumatic childhood during which most of his family, including his parents, were slaughtered at Constantius II’s command. (8) Scholars maintain that Julian manufactured the claim his soldiers pressured him in his quest to exact revenge and overthrow his cousin. (9) He did so through a letter-writing campaign that manipulated the facts—his desire to rewrite his own narrative nothing new, of course; it’s a human trait to want one’s life-story to be flattering. This is particularly true when the ego is as aggressive as it is in power-hungry men—as we know all too well given our current political climate.

Historians do not doubt that Julian was intelligent but he is seen as a failure by many biographers, not only as a Roman Emperor but as a Greek philosopher, which was another of his aspirations. That said, his story is seen as valuable because he left a thorough account of the struggles that defined his times. Even an author as critical of him as Browning could not deny the man had something special: “His character possessed a nobility that makes him shine out like a beacon among the time-servers and trimmers who so often surrounded him.” (10) Julian would rule for only nineteen months before being mortally wounded in a battle in Phrygia, a Persian city in modern-day Turkey. Libanius, one of his few true friends, wrote Julian’s funeral speech. The Greek teacher of rhetoric honored his fellow pagan by calling him a defender of gods and converser with gods—high praise for a lover of Hellenism. (11) Proving how fickle humanity can be is the fact that it was only a few centuries before Julian was scorned for his beliefs that Christianity was considered the illegal movement. What a difference several hundred years can make when the long narrative of history begins to fill in! Browning summed up Julian’s predicament so eloquently in his epilogue to the emperor’s story: “In a sense all historical figures are tragic for us, since we know what was for them unknowable—the future.” (12)

Today’s salon question is: Do you agree with Browning’s premise that being blind to the future brings a tragic element our stories when seen in a historical context?

A version of this piece was published in my book The Modern Salonnière. You’ll find it ,my latest book Lives Illuminated, and all my books on my Amazon author page. Print versions from Bookshop.org are linked here. You’ll also find a number of them on Kindle. To see the sources for the footnotes, click through to my footnotes page.

I've never been to this museum. As a fan of Gore Vidal's novel Julian, I'm intrigued to learn of the site's connection to the last pagan emperor. I've now put the place on my list for my next visit to Paris.